Adverse childhood experiences and their effect on lifelong health

By Caitlin Suginaka, M.P.H.’13 and Barbara Dietrich Boose

Imagine a world where rates of hypertension, heart disease, lung disease, mental illness, HIV, arthritis, asthma, cancer, stroke and many other leading health problems were cut in half. What result might that have on our health care costs, on productivity, on our overall satisfaction of life?

Now imagine a world where child abuse, neglect and household dysfunction were eliminated outright.

A growing body of research shows that these two worlds are one in the same. Eliminating toxic stress among children would have a profound impact on the health and well-being of individuals and entire populations.

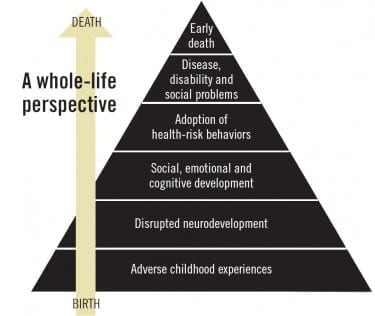

Adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, have been found to have a major impact on overall adult health. ACEs include physical and psychological abuse and neglect of a child, parental substance abuse, imprisonment or mental illness of a household member, violence or parental separation and divorce. These experiences dramatically upset the safe, nurturing environments children need to thrive and impact social, cognitive and emotional functioning throughout a person’s life. They also have been linked to poor health behaviors, chronic disease and even early death.

“That ACEs and chronic stress early in life lead to poor health outcomes is fairly well accepted. Understanding the mechanisms by which ACEs lead to physical, social and psychological outcomes is where the research is going,” says Rachel Reimer, Ph.D., assistant professor in DMU’s master of public health program. “It’s not 100 percent clear how ACEs are affecting health outcomes, but the fact there’s a very clear link between both suggests ACEs cause physiological and anatomical changes in our brains.”

A groundbreaking study published in 1997 by Robert Anda, M.D., and Vincent Felitti, M.D., found a strong dose-response relationship between experiences in childhood and health in adulthood. Conducted by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente in San Diego, the study collected data from more than 17,000 patients that clearly showed that ACEs were common; that they had a profound negative effect on health and well-being; and that they were a prime determinant of past, current and future health behaviors, social problems, disease incidence and early death in the study population.

The study has since been replicated in a number of states through the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a questionnaire developed by the CDC to collect state-level data on behavior.

“In the original study, 60-plus percent of respondents had at least one ACE; 12.6 percent had four or more,” said Nadine Burke Harris, M.D., FAAP, M.P.H., during a presentation on ACEs on the DMU campus on Oct. 14. “Their health outcomes were not just bad marriages or feeling sad, but they had diagnosed issues like heart disease and chronic pulmonary disease. ACEs had a higher relationship to negative outcomes than factors typically evaluated in medical examinations.”

Burke Harris is the founder and chief executive officer of the Center for Youth Wellness in San Francisco, which provides multidisciplinary care to treat chronic stress and trauma with comprehensive case management, mental health services, family support services, holistic interventions and education advocacy. The center’s goal is to develop a clinical model that recognizes and effectively treats toxic stress in children, connecting them not only with medical treatment but also social services such as counseling, stress-reduction therapies and family support.

“When you have a four-year-old getting kicked out of preschool and you don’t ask what’s going on in that child’s life, there’s something wrong,” she said. “What piece are we missing?”

Scientific evidence tying ACEs to poor lifetime health outcomes has enormous implications for everyone. Individuals suffer a poor quality of life. Schools struggle to manage and educate troubled kids. Communities experience crime and homelessness. Judicial and prison systems are forced to handle a growing population. And nations pay the price for increased unemployment and incarceration rates, rampant chronic disease, weaker economies and strained social safety nets. In other words, the issue cuts across all demographic and socio-economic lines.

“Each of us knows someone who’s been affected by adverse childhood experiences. They clearly affect almost every social, economic and health issue in society,” says Suzanne Mineck, president of the Mid-Iowa Health Foundation, which commissioned a study on ACEs in Iowa that was released last October. “It’s not just a dotted line; it’s a direct link to chronic disease and many other issues.”

What are the costs of preventing and reversing adverse childhood experiences? What are the costs if we don’t?

Given the direct tie between ACEs and poor health outcomes and the high cost of those outcomes, what can we do to prevent and counter them? How can we help not only the children in abusive or dysfunctional situations, but also the adults around them? What will be the costs of addressing ACEs?

More important, what will be the costs if we don’t?

The high toll of toxic stress

Real or perceived threats cause the body to set off an alarm system that releases a surge of hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol. For individuals under strong, frequent or prolonged stress, this “fight-or-flight” response stays on, disrupting almost all body processes, from immunity to digestion to brain development. It’s especially harmful to very young children, whose their brains are undergoing a period of very rapid development.

“Increased cortisol levels are great if you see a bear in the woods; you need to flee,” Burke Harris said during her campus talk. “But it’s harmful if the bear is coming home every night or waiting for you when you get off the bus every day. If you redline your engine every day, you’re going to need a new engine.”

The Iowa ACEs study showed that 55 percent of Iowans have experienced at least one ACE prior to age 18, and one third of all adults have experienced two or more. Adults who reported an experience of four or more ACEs were six times as likely to be diagnosed with clinical depression and more than twice as likely to rate their health as “poor.” They also were four times as likely to report HIV risk factors and almost four times as likely to be diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“These data highlight the significant impact traumatic experiences have on a child’s developing brain and are essential to informing policy and practice changes that can lead to better health for all Iowans,” Mineck said in a news release about the Iowa ACEs study. “Our hope is that this research inspires a commitment by communities to diminish the number of children exposed to highly stressful situations and build compassion for those who have experienced ACEs.”

When a young child’s stress response is activated, it can be buffered by protective factors, such as a supportive adult relationship and safe, predictable environments. These protective factors support the development of healthy stress responses and coping mechanisms. Without those buffers, toxic stress, or strong, frequent or prolonged activation of the body’s stress management systems, a child’s brain development is disrupted. Their stress response systems remain in overdrive and, consequently, their brains and bodies develop differently.

Some more immediate results may include hyper- or hypoactive physiologic stress responses, reduced temporal lobe activity, difficulty with attention or attachment disorders.

“We have increasingly good scientific data that say it isn’t just that you’ve had bad experiences that have affected your life; you’ve had bad experiences that have changed your brain,” says J. Jeffrey Means, Ph.D., M.Div., DMU chair of behavioral medicine. “Early trauma in the first three to six years of life have especially devastating effects on brain development, which has all kinds of ripple effects later.”

As a child in a chronically stressful situation matures, he or she may be more prone to cope using external substances or experiences such as smoking or illicit substance use, unhealthy relationships and binge- or under-eating. These behaviors may affect a person’s lifelong health. Their inflammatory responses are also heightened and, even without exhibiting unhealthy behaviors, they may still be prone to chronic health conditions such as hypertension.

Addressing ACEs: now what?

Knowing the impact that adversity in childhood has on our health, what can we do about it?

Consider an analogy: In the 1980s, little was known about HIV. A patient diagnosed with HIV at that time lived a matter of months on average. Over the course of a few decades, we have now reached a place where we are aware of the disease’s progression, we are capable of reducing its spread, it can be easily diagnosed and we have developed pharmacological therapies that can keep an HIV-infected person alive and relatively well for decades with proper care.

We are still at the very early stages of understanding the root causes of ACEs; more research in effective treatment is needed. However, health care professionals can take actions immediately that will have a dramatic impact. The fact that adverse experiences directly affect a person’s physical, mental and emotional health means they should be part of each patient’s screening and health history.

That’s easier said than done. The multidisciplinary treatment protocols that Burke Harris and her colleagues use in their clinic “do not fit in today’s health care model,” notes Carolyn Beverly, M.D., M.P.H., assistant professor in DMU’s master of public health program.

“Physicians often don’t have the time to help patients with ACEs,” she adds. “It goes beyond the children with ACEs, too; we also have to address the problems their parents and other adults around them may have. It will require health care, public health and social services to work together.”

Mineck of the Mid-Iowa Health Foundation notes the importance of making sure physicians, especially those in pediatrics and family practice, know what resources exist for vulnerable patients and families.

“If a physician asks the question to determine whether a patient has had adverse experiences, then what happens? The more we can connect them with resources that do exist in a community, then they will understandably be more comfortable asking the questions,” she says. “I hope physicians see themselves as frontline responders to this issue.”

For health care professionals who work with troubled youth, critical steps are gaining their trust and intervening as soon as possible after trauma.

“For children who go several months after trauma, recovery is much more difficult,” says Sasha Khosravi, D.O.’01, pediatric hospitalist and medical director at Mercy Behavioral Health Child and Adolescent Services in Des Moines. “We try to give them coping strategies and communication skills and address their cognitive distortions. A lot of kids feel they’re alone; then they sit in a group with 10 other kids and realize that others are fighting the battle. That gives them a sense of relief.”

Khosravi and his colleagues also work to give patients and their families a “sense of hope.” He himself is a compelling case: He grew up in Iran in the 1980s during the almost eight-year war against Iraq. “I had a lot of exposure to bombings and a lot of relatives lost,” he says. Later, as an undergraduate at Iowa State University, he worked as a counselor at a social services agency. “I ended up really liking these children who were basically abandoned.”

Limits on length of hospital stays, the stigma of mental illness and a “great shortage” of pediatric psychiatrists and psychologists, Khosravi notes, are problems in helping children in need. As a mental health consultant for the Des Moines Public Schools, he’s worked with East and Lincoln high schools to establish “mental health classrooms” that offer therapeutic environments for students struggling to function in regular classrooms. That’s one example of trauma informed care, a strategic approach in recognizing and treating the symptoms of adverse events.

Become “trauma informed”

Trauma is any experience that leaves a person intensely threatened. It often triggers physical, psychological and emotional symptoms. Examples of trauma include adverse childhood experiences, loss of a loved one, physical or bodily harm, or other events that threaten a person’s safe, stable environment.

Healing from trauma can take place in both clinical and non-clinical settings. Merely understanding trauma and its aftermath can help build a brighter future for trauma survivors, including the many Americans who have suffered adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

According to Gladys Noll Alvarez, LISW, coordinator of the Trauma Informed Care Project of Orchard Place Child Guidance Center in Des Moines, trauma informed care (TIC) is an organizational structure and treatment framework that involves understanding, recognizing and responding to the effects of all types of trauma. Trauma informed care also emphasizes physical, psychological and emotional safety for both consumers and providers, and it helps survivors rebuild a sense of control and empowerment. It is a way to relate to others that changes our thinking from “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?”

Alvarez says becoming “trauma informed” means recognizing that people have often experienced many different types of trauma in their lives, and those who have been traumatized need support and understand-ing from those around them. Trauma survivors can unintentionally be re-traumatized by well-meaning care givers and service providers.

Orchard Place’s Trauma Informed Care Project, which began in 2010, seeks to educate communities and professionals about the impact of trauma on clients, co-workers, friends, family and even ourselves. Understanding the impact of trauma is an important first step in becoming a compassionate and supportive community. Visit www.traumainformedcareproject.org for resources and ideas to help you and your organization respond to trauma and become trauma informed.

Perhaps ironically, allies in health care, social services, education and law enforcement may be better armed today to convince policy makers and elected officials to take action because of two grim realities: the increasingly clear and growing evidence of ACEs’ impact on long-term health and the rising rates and costs of chronic disease. In her campus talk, Burke Harris compared it to efforts in the 1960s and 1970s to tackle lead poisoning.

“When physicians would see kids with lead poisoning in clinic, they started to do regular screenings. The sources of lead were lead paint and leaded gasoline,” she said. “They had to convince paint manufacturers to take the lead out of paint, and car manufacturers to make cars that would run on something other than leaded gasoline. They resisted, but with data, research, policy and legislation, that ultimately happened. You can change systems.”

The Central Iowa ACEs Steering Committee, which includes the Mid-Iowa Health Foundation, the Iowa Department of Public Health, United Way of Central Iowa and other organizations engaged in children’s health and wellness, stated in the Iowa ACEs study: “The responsibility to prevent ACEs before they happen resides with each of us individually and collectively. When trauma does occur, it is imperative we respond with compassion, effective interventions and supports, and trauma informed treatments.”

“There isn’t an individual or a community that shouldn’t be aware of ACEs,” Mineck says. “We need to continue to invest in and be more aggressive in child abuse prevention, trauma informed care and family support not just from a systems standpoint, but from a community standpoint and a neighbor-to-neighbor standpoint.”

Going forward

The Iowa ACEs study, released last October, invites “communities, educators, systems, neighborhoods, social service agencies, religious organizations, medical professionals, police officers, social workers, cities, clubs, judges, parents, mentors, business leaders, policy makers, counties, philanthropists, insurers, [and] grandparents” to tackle ACEs in the following ways:

- Increase awareness of ACEs and their impact.

- Knowing the relationship between past experiences and coping behaviors, respond to one another with better understanding in our daily lives.

- Remember that everyone can help provide safe, stable home environments and loving relationships to foster healthy brain development and prevent negative life-long health outcomes.

- Advocate for family-based strategies that support parental resilience, social connections, parenting education and concrete support.

- Strive to build communities in which people feel a sense of responsibility and care for each other.

- Increase early identification of and response to ACEs across systems including health care, education, justice, social service and public health.

- Integrate a trauma informed approach across child and family serving systems and organizations.

- Support funding of the continued collection, analysis and dissemination of ACEs data.

For more information

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Study

- Iowa ACEs study

- ACEs Too High, a source for research, statistics, news and information about efforts of communities, states and organizations to reduce the impact of ACEs

- Academy on Violence and Abuse

- National Center for Children Exposed to Violence, a source for information, training and collaborator in supporting the reduction of violence against children and families

- Too Small to Fail, a joint initiative of the Next Generation and the Bill, Hillary and Chelsea Clinton Foundation promoting actions to improve the health and well-being of children ages zero to five

- Zero to Three, a national nonprofit organization that provides parents, professionals and policy makers the knowledge and know-how to nurture early development

- The Trauma Informed Care Project of Orchard Place Child Guidance Center, Des Moines, a source for health care professionals, parents, educators and others on evidence-based trauma informed services